The Impact of COVID-19: A Transitional-aged Young Woman with Anorexia Nervosa

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to look at how public health interventions to lessen illness and loss of life may affect patients struggling with eating disorders. One change that often follows treatment disruption is that patients return to their pediatric primary care provider to rebuild the care team and create an effective treatment plan. Let’s look at one case example for illustration.

Jessie is a twenty-year-old college sophomore with a history of restricting Anorexia Nervosa in high school. Now in college on a volleyball scholarship, she and her teammates had a stellar fall athletic season and became a cohesive circle of friends. Her coach was a strong benevolent father figure she relied on for structure and routine. Jessie was able to maintain a 4.0 GPA in her studies and, with the help of an on campus Eating Disorder program, felt that her restrictive eating disorder was under adequate control.

In early March, with the arrival of the COVID-19 virus pandemic, her campus was closed so she reluctantly returned to her hometown out of state to live with her mother and a younger brother. Although her family had participated in Family-Based Treatment (FBT) during her senior year of high school, they had not been able to move to a phase of increased autonomy while she was still at home. Going out of state for college, establishing a treatment team on campus, living in the dorm and volleyball had allowed Jessie an opportunity to experience a measure of autonomy outside of her family.

So how did the COVID-19 pandemic affect Jessie?

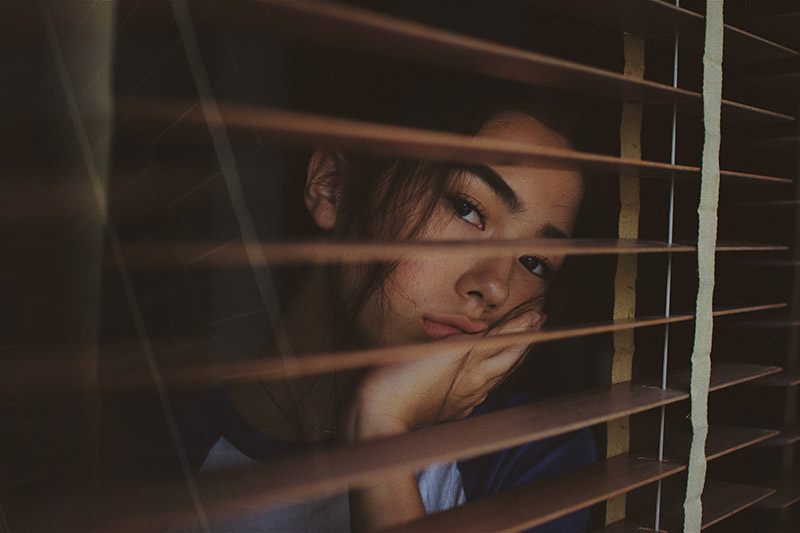

Facing all of these challenges, Jessie felt anxious and out of control. She secretly tightened her calorie intake and began to lose weight. She became irritable and depressed and stopped making an effort to connect with her college dorm friends and teammates. She decided she would run alone every morning on her old high school track to maintain her weight and conditioning, gradually increasing her mileage without changing her limited food intake. Her telehealth therapist continued to work with her once or twice a week to rebuild a treatment plan that still included the Registered Dietician from the campus program but pieces of the team were missing. Together with Jessie, they initiated the following:

The COVID-19 pandemic is disruptive and frightening and has had an impact on each of us. Patients, families, providers and whole communities have had to be creative and resourceful to manage this “new normal”. Individuals with Eating Disorders and their families face several unique challenges that require careful consideration. Thoughtful, collaborative work between families, re-involved hometown primary care providers with Project Teach consultation, local mental health providers, coaches and others can rebuild the “village” to support young women like Jessie to not only survive, but to grow from these challenges.

Jessie’s case illustrates the remarkable adaptation behavioral health services have made due to the need for social distancing through telehealth. With the critical relaxation of state regulations and privacy requirements, technology has been rapidly adapted to address the physical and mental health of individuals with psychiatric illnesses. Pediatric Primary Care Providers in New York State have long enjoyed access to free phone consultation warm lines, remote telepsychiatry evaluations, and referrals to community resources, available through Project TEACH. Flexible, creative, collaborative approaches like telemedicine and psychiatric phone consultation to primary care are lifesavers for specific vulnerable groups during unusual adverse conditions such as during a pandemic. They also offer lessons to help us provide more effective modes of service when the pandemic eventually ends.