The COVID-19 global pandemic has profoundly changed how we interact with each other. The lack of in-person social interaction has left many children and teens feeling isolated from their peers and families. Children and teens may not be affected physically to the same extent as adults by SARS-CoV-2 but they certainly have been emotionally.

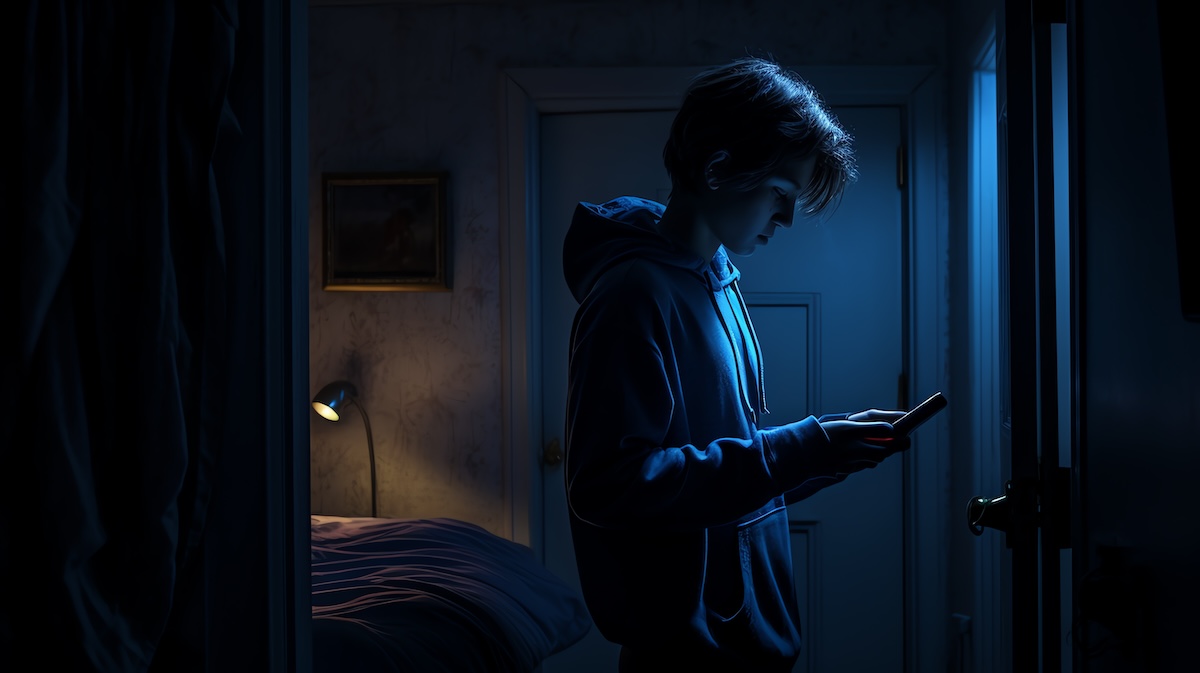

While physical bullying has decreased during the pandemic, the opposite is true for cyberbullying. Given the increased amount of time our children are spending in front of electronic devices for both educational and recreational purposes this should not come as a surprise to anyone. According to L1ght–https://l1ght.com–an organization that monitors online toxicity and harassment, there has been a 70% increase in cyberbullying since the pandemic began. L1ght also found a 40% increase in toxicity on online gaming platforms, a 900% increase in hate speech on Twitter directed toward China and the Chinese, and a 200% increase in traffic to hate sites. Unlike traditional bullying, which stopped at three o’clock when school let out, cyberbullying occurs 24/7. Free time in quarantine has led to more leisure activities like online gaming and accessing chat rooms and social media platforms such as Tik-Tok, Instagram and Facebook. A 2019 study from the Cyberbullying Research Center– https://

Cyberbullying is defined as “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones and other electronic devices.”

Cyberbullying includes:

Increased stress from COVID has put everyone on edge, and children and teens are no exception. As a result, hostility towards others has increased. Teens manifest this hostility through self-preserving and self-defensive interactions with peers online. The pandemic has brought a new form of online exclusion called “cancel culture” where an individual is suddenly excluded from a group or friend circle by the cyberbully. Emotional immaturity results in lashing out at others. Misunderstandings even among friends occur because someone feels they are missing out or being kept out of the loop. Some teens engage in cyberbullying simply out of boredom, loneliness or need to feel important. Many teens don’t realize that trying to be the new Tik-Tok star at the expense of a friend or schoolmate is extremely unhealthy with potentially serious consequences.

We are all well aware that the pandemic has brought a dramatic increase in mental health issues such as depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety and PTSD-like symptoms. Those children with existing mental health problems are also at higher risk for exacerbation of their depression and other mood disorders as a result of negative online experiences.

The COVID-19 Collection in PEDIATRICS July stated: “Given the increased risk of trauma exposure, as well as anxiety and grief, during and after this crisis, identifying and managing anger and stress that affect family interactions, screening for PTSD symptoms and providing practical resources as those published by the AAP and National Child Traumatic Stress Network are warranted.”

Many families are dealing with issues other than cyberbullying, including food insecurity and loss of income because of the pandemic. So what can we as pediatricians do to help our patients during this trying time? It starts with asking the simple question: “ARE YOU OK”? We have to start the conversation about cyberbullying and be prepared to listen.

We must educate parents to watch for signs of bullying in their children, including:

Pediatricians need to support parents when talking to their children about:

We must encourage parents to contact teachers and school administrators to ask what the school’s plan is to continue social and emotional skill-building for students during remote learning. Helping students gain social coping skills, and providing assertiveness training fosters resilience and serves to keep students safe. Administrators are often willing to intervene, since out-of-school aggression among students can negatively impact the safe social environment they are trying to create within school.

Talk to parents about an app called “RETHINK”. Once downloaded it encourages the teen to think before sending a message or an online post. Children and teens can be impulsive, but teaching them to think before sending is a great way to prevent toxic messages or videos from being sent.

In our role as advocates for youth we must help our patients and families not only stay healthy during the pandemic but maintain positive mental health.

Child

Child